The two days symposium held at Tate Modern gathered numerous prominent speakers. The quality and range of interventions was uneven. Nevertheless, a few contributions were capital in re-addressing and energizing old exhibitions and debates that keep coming back in contemporary discourses. While the fever for the 60s and 70s is still high, this symposium offered some keys of interpretation in judging why, and offered some inspiring tips on how to be creative in a time of economical recession.

In her presentation, Lucy Lippard declared that she never considered herself a critic, but a writer. This is because of her proximity with the artists she was writing about and doing exhibition with – she was part of the amazing circuit of New York based artists in the 60s and 70s, and not an external critical figure. Another reason is that she always thought that life is too short to invest time writing about topics or artists you dislike or are not interested in. As I share Lucy Lippard’s view, I will only briefly discuss the interventions and discussions that I found more fascinating and inspiring in the understanding of past and present artistic debates.

One of the most exciting parts of the symposia has been the session ‘ Not exhibitions’, with presentations by Daniel Buren, Lynda Morris and Guy Brett.

Daniel Buren discussed numerous works that, from 1967, revolutionised the way we think of exhibitions, constantly pushing the boundaries of where and how it is possible to exhibit art, complicating the relationship between art and life, and constantly maintaining a critical approach that fought the feeling ‘we are doing the right thing’ just because of the context or modalities chosen for the installation of the work. The works presented strike for their temporal dimension, for the exhibition of the process, and for their coherence, in constantly elaborating a practical theory in art. Critically, Buren constantly challenged all limits imposed to an artist and his work. He has been, despite his will, defined as leader of the ‘institutional critique’ artists, who would exit the museum as a critical response to the fixed, interpretative frame of the museum. Yet, it is not only the museum that Buren criticized, but all contexts that would be used without challenging their nature and unwritten rules. In an interview from 1971, filmed by Jef Cornelius on the occasin of Sonsbeek 1971 (and screened during the symposia as part of Koen Brams’ session), Buren criticize the attitude and implicit idea that showing art outside the museum is per se good and reflective of a critical stance – he points out that you can be outside the museum and produce works which is critically empty. This is why, in that circumstance, he decided to show in the museum. He raised very early issues that only more recently have become major topics of discussions within the art world. For his first solo show in a museum, in 1971, he asked to only show his work around the permanent collection. During the exhibition, the hunging of the permanent collection was changed, but the paoer stripes were kept in the same place. While making visible the traditional and constantly repeated way of exhibiting art in a museum, and creating a sticking juxtaposition of more traditional art and contemporary artistic strategies, the exhibition acquire a further temporal dimension, and subvert the static dimension of museum displays. One year later, he was ready to challenge the approach of the man who was already recognised as the curator of our time: Harald Szeemann. In his text for the catalogue of the 1972 Documenta 5, he lamented the fact that, more and more, the subject of an exhibition tends not be the display of artworks, but the exhibition of the exhibition as a work of art. He remarked that the exhibition establishes itself as its own subject, and its own subject as a work of art, while the curator (then named exhibition organizer) becomes the author. Buren declare that: ‘the limits art has created for itself, as shelter, turn against it by imitating it, and the refuge that the limits of art had constituted are revealed as its justification, reality, and tomb’. This passage is incredibly revealing of Buren’s attitude throughout his career: the refusal to accept limits and expectations that turn art works into objects, and cristallise the interpretation of art within fixed rules. His approach is to constantly revert expectation, and constantly keep open the question of what makes art art and how we relate to it, physically and critically.

Lynda Morris made a precise and inspiring presentation on the role of dealers in the development of conceptual art in its first decade, 1967-1977. Taking as a starting point data from the research of the late Dr Sophie Richard, Morris argued the importance of exhibitions in Northern Europe in establishing the reputation of American artists and, in particular, the role played by the most important dealers in this initial phase. Lynda Morris defines these dealers, first of all Konrad Fischer, as curator-dealers, who had a huge impact on the work shown by other prominent exhibition organizers, and on the works collected by major museums in Europe at that time. The data collected by Sophie Richard, show that most museums in Europe, between 1967 and 1977, would shop at Konrad Fisher gallery. This proves the massive role that the German dealer had not just in presenting, for the first time, American Minimalist and Conceptual artists, but also in creating a formidable network of artists, curators and Museum directors, securing major exhibitions and a place in important collections to many of the artists he represented. Morris’ presentation was quite moving, for her desire to stress and remember the importance of the role played by an old friend in the development of a field she master. Moreover, Morris is attempting a major revision in the recent history that has positioned curators as the puppet player of contemporary art. Morris is trying to show how the intellectual elite of museum directors and freelance curator has actually been following for decades the leading role of important dealers who were not just players in the art market, but protagonist in shaping the history of contemporary art. Apart Konrad Fischer, other important dealers who played such a role in the late 60s and 70s are Paul Maenz, Heiner Friedrich, Anny de Decker, Fernand Spillemaeckers, Art and Project and Nicholas Logsdail. Morris is asking a bit of honesty and, maybe, humility, on the part of critics and curators, in acknowledging the fact that certain art dealers have played the most important part in recognizing the incredible artistic shifts that was taking pace at the end of the 60s, and were able to create a vital network of artists, and were, often, their closest friends.

Guy Brett gave a presentation titled ‘The Elasticity of Exhibition’, in which he addressed one of the strongest taboos in contemporary art: the concept of the poetic. He gave numerous examples of the poetics in exhibition making, starting from Yves Klein’s Le Vide, 1858, which constituted a landmark in the history of artworks-exhibitions, while being one of the first contemporary art events with an enormous response in terms of number of visitors and media coverage. Another memorable exhibition at Galerie Iris Clert in 1958, was a collaborative work by Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely: the installation Vitesse pure et stabilité monochrome (pure speed and monochrome stability). The works combined Klein’s use of monochrome with the mechanical and dynamic nature of Tinguely’s art.

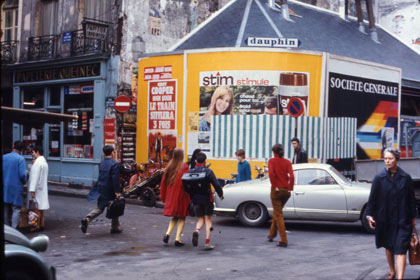

Brett’s presentation also felt as an attempt to revert the traditional concept of ‘landmark exhibition’, offering example of projects of a fleeting nature, and attempting to bring to the general attention works and exhibition that, because of their temporal and temporary nature, never entered public museum collections and tend to be more easily forgotten. Examples span form Alberto Greco’s Vivo-Dito, from 1962, to Vassilakis Takis’ The Impossible – A Man in Space, 1960, Iris Clert Gallery, Paris. Takis was known for the use magnetism to suspend forms in space. In the case of The Impossible – A Man in Space, Sinclair Bells is the one who levitates in the emptiness, while reciting one of his poems called ‘I am a sculpture’. The photographic documentation of Takis’ work opens to its incredible potential. Investigating the expressive power of invisible forces, impossible becomes possible and the logic of our functioning on Earth

points to a different way of being in space.The exhibitions discussed by Brett span from Cildo Meireles’ Fiat Lux, O Sermão da Montanha (Fiat Lux, the Sermon on the Mount), 1979, to Susan Hiller’s Work in Progress, Matt’s Gallery, London, 1980, to Gabriel Orozco’s Empty Shoebox, 1993, “abandoned” on the floor of gallery spaces. The last fascinating project mentioned by Brett was Colecção Manuel Brito (Manuel Brito Collection), realized by João Penalva at the Museu do Chiado, Lisboa, 1994. For this project Penalva adopted strategies that have been since repeated numerous times, mixing reality and fiction within an exhibition display that claimed to exhibit artifacts from a private collection. All these examples are of works of an ephemeral nature, events where the art objects or performances were the starting point for a reflection, which offered instruments for reading the work in different terms.

The numerous exhibitions and writing of Lucy Lippard are quite well known. What was most sticking about her talk was the completely un-monumental way of presenting her projects and talking about her life. She mentioned the time she was living with Seth Siegelaub, and how the ‘Do it’ of Hans Ulrich Obrist was at the time a truly DIY way of doing things, without desire or intention off climbing the art world ladder. She showed images of many well-known works, as well as some wonderful works unknown to me, such as a piece by Rosemarie Castoro, presented at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1966, in which a light, positioned in the centre of a room, would go dimmer and dimmer, and then bright up again. Lippard also discussed the obsession of his generation with issues of time, space, body and lived experience. She mentioned Sol LeWitt’s definition of ‘idea chain’, for which ideas would pollinate from the work of an artist to the one of another. Artists would also present or incorporate the work of other artists, while there were a great overlapping of roles among artists, writers and curators – her ‘curating by numbers’ was in fact directly influenced by the structural approach of artists. Yet, Lippard was reticent in defining herself a curator: her exhibitions were born, as her essays did, from visiting many studios, meeting and discussing with many artists, and going through a process of selection, as a response to a situation. She also discussed her shift of interest from Conceptual Art, to Feminism, to collaborative movements. Feminism, that she describes as a life change, meant that she wanted to go back to the art world, to try and influence it. It was a time when her exhibitions were ‘intentionally scruffy’, she says. In the late 70s, her interest in collaborative practices was inspired by the work of young collectives, and represented a shift in attempting to have a social engagement with the real world.

To me, the greatest lessons of this symposium were the examples of lives devoted to criticality and uncompromised in their passion an ethical stance. As Vasif Kortun said, the economical recession we are undergoing feels like a bit of a blessing. So many artists and institutions seems to have been sucked in and paralised by the idea of where we should be going (all in the same direction) and why (money, growing production, more exhibitions around the globe). Lynda Morris, Guy Brett, Daniel Buren and Lucy Lippard represent to me some of the truly uncompromised and critically aware stars of our cultural landscape, and wonderful examples to follow.